"Yukon" means "great river" in

Gwich’in, and this word became the name of the Yukon Territory. The Yukon River is one of the world’s fabulous and grand waterways; not as well known but equivalent in its way to the Ganges or the Mekong. All these great rivers arise in faraway mountains, then travel across continents, and end up somewhere else altogether.

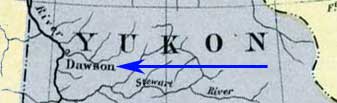

In the case of the

Yukon River, its headwaters are close to the Pacific Ocean, then it cavorts every which way for thousands of miles around northern Canada collecting the tribute of tributaries before coursing across Alaska and emptying into the Bering Sea. In the gold rush days, especially between Dawson and Whitehorse (that is to say, between Dawson and the Outside) the Yukon River was the main transportation and supply route, at least during the six months of the year between break-up and freeze-up. The river was a lifeline, but for those who fell into it, it was the end of the line.

Starting with Frank Berton, who left New Brunswick and made his way to the Klondike in the gold rush, Berton family members have made several memorable trips on the Yukon. In

Drifting Home (1973), which the

Canadian Encyclopedia describes as "an unexpected slice of autobiography in the form of an account of a northern rafting trip," Pierre Berton recounts generations of family stories, triggered by this river journey through a landscape rich with history and a terrain equally evocative of a frankly ruthless timelessness. The North and the Yukon are both harsh and beautiful; unforgiving and compelling.

In Canada we tend not to appreciate our wild spaces, perhaps because we have so many and have felt little need to conserve them. Survival has often been a concern more pressing than conservation. During his rafting trip, Pierre Berton predicts a future for eco-tourism in the North. The most precious natural asset "is no longer gold, silver or base medals — although many Yukoners still cling to this idea. People in the urban south are hungering for the wilderness and the more they crowd into the cities the more they want to get away. Here, the wilderness rolls on, like the river, for hundreds of miles."

In the future, the question is whether civilization will turn this river into a sewer, or will a generation yet to come, "wiser than ours, find some way to preserve these waters for the children who follow?"

This question is one with a universal application, and this trip connects generations of an adventurous Canadian family, in a journey through a landscape framed by history yet mindful of the future.

In a place where the river has eroded the banks, the steamboat charts identify a white smear about a foot beneath the surface as

Sam McGee's Ashes. Along with other fanciful creations, such as the moose meat at the Lake Bennett train station and bits of spaghetti added to ice cubes (known as ice worms), the North is full of stories which are equal parts myth-making, confabulation, tenderfoot teasing, and ambiance. But also, always buried away like the fabled elusive mother lode, is the truth. It is good to keep in mind that truth is stranger than fiction.

Ice worms, if you can believe the internet, turn out to be real, and not just the subject of a ballad by

Robert Service. The layer of volcanic ash, several feet thick in places and representing an awesome eruption, originated 1200 years ago from what is now

Mount Churchill, near the Yukon-Alaska border.

DAWSON CITY

DAWSON CITY This is the entrance to the Berton House Writers' Retreat. The childhood home of author, journalist, broadcaster and Canadian icon, Pierre Berton, the

Berton House Writers’ Retreat has been accommodating

writers-in-residence since 1996.

This is the entrance to the Berton House Writers' Retreat. The childhood home of author, journalist, broadcaster and Canadian icon, Pierre Berton, the

Berton House Writers’ Retreat has been accommodating

writers-in-residence since 1996. BERTON HOUSE

BERTON HOUSE YUKON RIVER

YUKON RIVER